Though my family owned ostensibly Italian restaurants, the reality was that the menu was far removed—if not unrecognizable—from true Italian cuisine. They were Chicago businesses. Try finding an Italian beef sandwich, or deep-dish pizza in Italy, and then prepare to be scoffed at and loathed.

Pizza in that brigade system was geared to a Ford-style assembly line production. It was not a specialized, Napoletana-style pizzaiolo that crafted each pizza one at a time. Instead it would be a line of guys, each performing a specific repetitive task that could keep the orders moving along with efficiency and without the huge investment of time required to create a dedicated master of a craft. This way it was replicable, and not dependent on the continued dedication of an immigrant workforce that didn’t have a cultural context for the craft and could be transient. It was nearly ten years until the business would start offering pasta, and then it was decidedly secondary to the main business at hand.

Because of the industrial-scale operation at the family restaurants, I learned almost nothing about cooking from my exposure to the business. And because my parents were hard-hustling operators, I was something of a latch-key kid in the kitchen. So beyond the thin, crispy chuletas that my mom would make, who’s garlicky round loin section served as the perfect utensil to scoop up beans, I didn’t get many recipes from my family.

Puerto Rican style fried Chuletas

Once I had graduated from watching frozen chickens defrost in the sink I moved on to PBS cooking shows. Yan Can Cook and the (now-disgraced) Frugal Gourmet Jeff Smith were my early favs. I remember the Frugal Gourmet had a big appreciation for Chinese and wok cooking, calling Chinese food one of the three great cuisines, alongside French and Italian. My dad also loved Chinese food, and his go-to favorite restaurant was the Pine Yard Chinese restaurant in our hometown. The food there was always excellent Cantonese—spicy chicken with peanuts, wonton soup, shrimp chow mein, and my favorite, bbq pork with snow peas. We would eat there for the next 30 years until the time we finally cut ties with the city. We lost our businesses and home in Chicago shortly before the Pine Yard burned down, never to reopen.

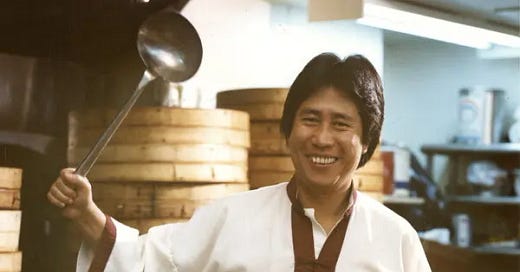

Martin Yan

As a kid growing up in the 80s, Martin Yan was a good entry point for approaching Chinese food. Though a lot of his grinning and schtick for the camera has definitely aged poorly, he was a transitional media personality for asian people. Kids today don’t know how outwardly racist and completely unconsidered brown people were by media and pretty much everyone who was ‘normal.’ Though I knew I wasn’t Chinese, there was someone I identified with and looked up to on Yan Can Cook.

Before I was 12, we’d gotten a hand hammered wok (as advertised on TV), and I had a moderate cleaver that felt so substantial and good in my hand. I would chop up garlic and ginger like the guys I watched on WTTW channel 11. I would read cookbooks—preferably ones with nice pictures—and start to get some underlying concepts together on how to approach cooking.

That being said, my palate has decidedly expanded since then, and I’m sure the initial level of my execution wasn’t too impressive. The simple stir-fries I made, accompanied by my mom’s recipe for rice cooker rice (one more cup of water than rice, a few tbsp. of oil, and a bit of salt) would not impress anyone who wasn’t overtly encouraging and sympathetic. In fact, even that rice recipe has raised the eyebrow of every asian person I have ever cooked rice for, but they never argue with the results of this Latino approach.

Beyond my early wok experiments, the thing I cooked most was pasta. At first I would quickly cook a few chopped cloves of garlic in oil at the bottom of the pan before adding Ragu or Prego store-bought jar sauce, plus oregano, and like that—Bam!—I’m cooking.

But that high didn’t last too long. Soon I started opening up tins of crushed tomato and investing the additional 20 minutes in simmering my own simple sauce. Sometimes I would add a little red wine from one of the leftover bottles in the fridge. I tried to put together more sauce and noodle game off the guys on TV, plus movies like Goodfellas and the legendary razor garlic technique (sadly, never faithfully attempted).

I liked to cook, and I was more practiced than most everyone my age, but that didn’t mean I was actually good at it. The truth is that any improvement and success is based on a hill of practice and failures. When that comes to cooking, it means there are a lot of disappointing meals that have to be cooked and eaten in order to get to the place where you can start to call yourself capable.

A whole lot.

And the sharp side of the knife is that the more you learn about food and cooking, the more curious and adventurous you become, the better your taste gets and then your technique needs to improve to catch up to your understanding. This creates something of a virtuous cycle that eventually gains momentum enough to mean the more I learned about food, the better I cooked, and the more food I could eat at an ascending level. Years of investing in the bouche along with the kitchen, and eventually your hands will execute well enough that your tongue will thank you.