Tragón

Since I was very small—like barely walking—I had a reputation as a hungry boy.

I went so far as to drag a chair out to the sink to climb up and watch the frozen chicken thaw in the sink.

‘Jason, what are you doing?’

‘Kicken, daddy,’ I’d point at the thawing bird, ‘Kicken.’

They gave me the nickname, tragón—basically translating to eater.

My family had pizza restaurants which my father named after my mother, Carmen. Spending my early years there around cooks, waitstaff, and customers, playing hide and seek with my brother in the catacombs beneath the kitchen among bags of flour and cans of tomato—this was the site of some of my earliest memories.

The restaurant business is very tricky. Even for successful operations, the margins are so slim and risks are so prevalent that the possibility of going out of business is never far. It only takes a few bad months to go underwater and lose it all. The stress that accompanies that industry is inescapable, and the tension that emanates from its burden is only unnoticed by the most oblivious members of a restaurant family.

Though I was aware of the pressure on my parents, who had a whole minor society of people that depended on them and had their livelihoods attached to them, I also got to indulge in the benefits of their success. Namely, pizza. Tons of it.

Pizza was the most common meal I would eat for my first 18 years. Probably three times a week or more. Being from Chicago, there was more variety in what was on the menu than other places. There was thin crust, pan, and stuffed.

Though the thin was still thicker than a NY style slice, it was nowhere near the depth of the pan. And in turn, the pan was less substantial than the stuffed.

Even in Chicago, there is a misunderstanding about the distinctions, and instead things get flattened by the general term deep-dish. As you leave Chicago, there is no hope for distinguishing between them at all. Forgive me for clarifying between them here:

Thin - Roll out the dough of some substance, add sauce, then toppings, then cheese. Cook 20-25 min.

Pan - Roll out the dough and place in a greased welled-pan whose sides rise at least 1 1/2 inches. Press the dough into the corners, sides and bottom and trim it off along the rim. Then add sauce, toppings, and a generous amount of cheese. Bake for 30 min or so.

Stuffed - Roll out dough and fill the pan as done above, but skip the sauce used in the two previous versions and instead add toppings and cheese. Then roll out a thinner layer of dough and cover the toppings. On top of this thin layer of dough goes a healthy amount of tomato sauce that is thinner than the pastier version used in the previous variations, and then a sprinkle a light amount of powdered parmesan cheese on top. This gets baked for 40 min.

To the untrained eye, the Chicago-style Stuffed pizza just looks like a tomato saucy mess of cheese. But this is ignoring the structural integrity that is being maintained by the layering and balance of construction within the pan.

Naturally, not everyone makes these dishes the same, and there is no consensus on very much at all in Chicago other than the 85’ Bears and Michael Jordan’s clear GOAT status, but this was the architecture of the pizzas my family raised us on to great success.

The shorthand in the restaurant used to communicate the orders included the Special (Sausage, Mushroom, Onion, Green Pepper), and the true house specialty, the stuffed spinach pizza—written on tickets as Popeye.

I ate more spinach than a hundred kids, but it was always minced and mixed with cheese, then layered on dough within the construction of a pizza (we never called them pies).

As I understood it, pizza was a healthy thing. It contained all the food groups, and since the integrity of our restaurant’s ingredients was irreproachable, there was no excessive oils or fillers that would clog up my guts with the foul additives that have sullied so much of the contemporary food industry. Just like Popeye, I ate my spinach and would be strong to the finish.

During the 80s the staff swelled and we had an extended family of employees and coworkers that were always present. Immigrants from Latin-America like my relatives, who had come to Chicago to try to earn money and find a life in the US, and eventually learned how to live off of the regional dish of that cold city.

And as I would walk into the restaurant, I would see their brown faces smiling back at me from above the counter of the kitchen, lined up in a brigade in front of the giant convection oven full of dozens of pizzas.

‘Heyyyy, Tragón!!’

And I would smile back and feel shy pride that I could be a part of the sweet and buttery rich culture that made us part of a whole.

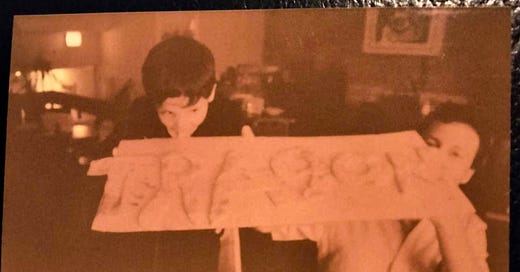

As a child in the family restaurant with my father, ‘Tragon’ written in pizza dough